Life Only Comes in Flashes of Greatness

And the old man sang:

It wasn’t a vintage year. The problems I outlined with MotoGP over the summer break in June were only exacerbated in the season’s back half by continued injuries (and here it’s worth not just considering how we didn’t have a single race out of 40 where the original starting lineup for 2023 took the grid, but why). They were exacerbated by the continued confusion over how Saturday sprint races are treated both by Dorna and the media (if you asked some journalists who should know better, they’d tell you 2023 was the first time since 1949 — MotoGP’s inaugural year under 500cc regs, as they then were — that we had no consecutive race winners … except both Pecco Bagnaia and Jorge Martin each had three weekend sweeps counting sprints, never mind Aleix Espargaro’s double in Barcelona or the various other Sunday-wins-followed-by-Saturday-wins across race weekends). They were exacerbated by tire pressure warnings and violations, which no one wants or wants to care about except Michelin and the people making those tires looking to save their own asses when something goes wrong. They were exacerbated by petty bickering over what to do about the aero problem, rules we’re supposedly “stuck” with until 2027. They were exacerbated by labyrinthine concessions updates. They were exacerbated by, first, Pecco Bagnaia living down to all my expectations of not really looking like he wanted a second championship even before his injury in Catalunya, then Jorge Martin trying too hard to win it away from him on Saturdays when victories were only good for half points because sprints but also because sprints; neither, in the end, looked particularly convincing as champions. But perhaps most distracting was how they were exacerbated by 2024. Every weekend Marc Marquez played coy and put off saying anything about his future was another weekend four or five other guys had to contend with the idea that they may be out of a job soon thanks to Pedro Acosta and their managers had better have been hustling to make sure every “T” on their contract was crossed, every “I” dotted. It was a throwback to the days when ink dried in the final weeks of the season, or even the first weeks of the offseason, that Luca Marini was finally announced as a factory Repsol Honda rider on the Monday after Valencia and that Fabio Di Giannantonio was granted a stay of execution after all with Ducati via a lifeboat from the VR46 squad. The Italians take care of their own the same way the Spanish do — and in Marquez’s case at Gresini alongside his brother Alex for a second try together after an aborted attempt in 2020, it’s going to be a case of Italians and Spaniards taking care of each other.

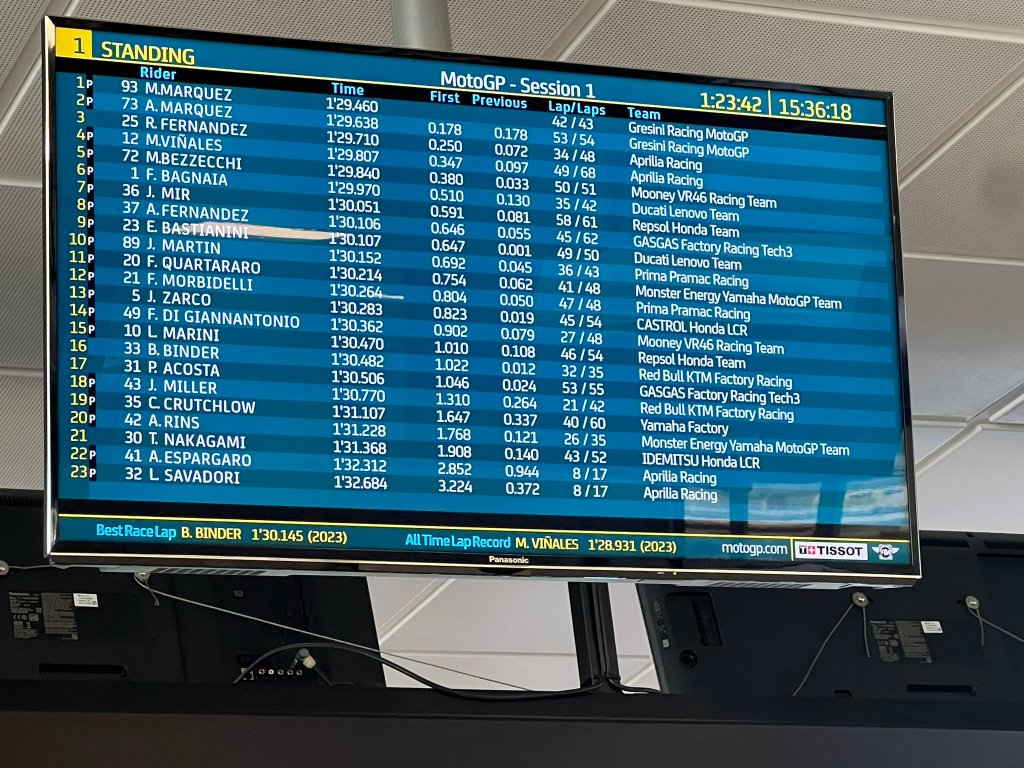

Which he already is, of course. How do we know the 2023 season wasn’t a classic? Consider: It took Marc Marquez seven laps to get up to speed on that Ducati Tuesday afternoon. It took 42 laps for the board to look like this:

And less than 48 hours removed, Pecco Bagnaia’s second championship is but a distant memory. No amount of Gavin Emmett’s forced enthusiasm or Neil Hodgson’s grin-and-bear-it color commentary can cloak it: No one cares. Maybe not even Pecco himself.

Yet amid this mess, a perceived inflection point where everyone agrees something has to be done but not how to do it — with MotoGP, the next great idea that’s going to fix the product and launch the sport into Formula 1’s orbit of cultural ubiquity always seems to be just out of reach, forever right around the corner — there is something to salvage, a reminder of the joy this bizarre and vicious spectacle can bring when it’s at its best. Even an increasingly jaded old fan can cherish two obvious exceptions to an otherwise lacking season.

And the old man sang:

American sporting audiences now know all too acutely this particular headache Euro viewership has been subjected to for decades, but go on, let’s ask the question anyway: Who put their money on it? No, really: Fabio Di Giannantonio? Who could’ve guessed? Well, aside from the type of person liable to make wild bets on a flier via mobile app. Aside from the whales of the world.

When I made the parenthetical that of Ducati’s riders this year, “any of them (even Fabio Di Giannantonio) could take a victory,” I wasn’t joking… but that “even” did a lot of heavy lifting and really, did you see Di Gi’s form as 2022 came to a close? Well, of course you didn’t: He was never near a TV camera. The kid looked lost. A brilliant pole at Mugello in front of his home crowd proving he had something to work with aside, Di Gi scored a single point in the last seven races and was, by a comfortable margin, the worst Ducati in the field — no, he was among the worst riders period in the field. Contrast that with the featherweight touch of his teammate, Enea Bastianini, who rode the same bike to four wins, a third place in the championship and a factory seat for 2023 at season’s end. The clock was ticking on Di Gi before this year even started. Any Moto2 boy willing to bring money up could have come calling.

And up until October’s Japanese Grand Prix, you’d have thought two years was enough, we’d seen what we were going to see out of Fabio. But just as the cards were folded and his fate evidently decided, the results came: Two eighths in the rain, a sixth and a fourth in India, his first podium earned in a brilliant scrap with the leaders in Australia, a couple of ninths despite looking competitive. There was chatter he, like everyone else, would end up at Repsol Honda taking Marc Marquez’s seat. There was chatter he might get a full-time test role. There was World Superbike chatter. There was chatter Ducati had found a place for him. A classic Toni Elias case, riding out of his skin with nothing to lose because it was contract time.

Except there was a fundamental change in that garage. Some credit must be due here to Di Giannantonio’s crew chief Frankie Carchedi, who finally figured out what the problem was: They were spending too much time reading the other Ducati riders’ data. Di Gi was trying to make his style work to the bike when what he should’ve been doing is making the bike work for him. It’s easy enough to say, but learning what makes you go fast is an art some guys never figure out.

Anyway, he did, conclusively, in Qatar beneath the lights where his former teammate took his first win for Gresini a year before. Enea Bastianini, beaten up and confidence battered, had just come off an improbable Malaysian Grand Prix victory with the factory Duke; here, under the Middle Eastern lights of a sand-ridden circuit, Fabio Di Giannantonio improbably slipped past Pecco Bagnaia in the dying laps of the Sunday main race to score his first, his only win. There couldn’t have been a dry eye in the house for one of the paddock’s nicest guys even if the ink looked dry on almost every contract for 2024… ah, but then.

Now he gets another season to justify that late-blooming form. He loses Carchedi to Marc Marquez, but he’s learned a few extra lessons just early enough to save his top-flight career for another season. And what do those lessons promise for the year ahead? Whatever it might be, there is this much to smile and look back upon: Fabio Di Giannantonio took it to the best in a straight fight and came out ahead. You have to laugh along with him, you have to shake your head to yourself. Who cares who could’ve guessed?

I was right. Even Fabio Di Giannantonio could take a victory. Fabio Di Giannantonio, a MotoGP race winner.

And the old man sang:

I was wrong. When I wrote of Johann Zarco in 2019 that “while I don’t think he’s gambled on the wrong decision for his career, that exciting moment in Qatar two years ago when he was slowly drawing away from the field before he crashed will probably remain, a fluke win on good strategy or a late-career surprise podium in the rain aside, the highlight of his time in MotoGP,” I couldn’t anticipate just how demoralized he’d become at KTM, a manufacturer now much better known for its ruthless rider churn — just ask Pol Espargaro, who lost that game of musical chairs thanks to Acosta and Marquez despite a contract in black and white saying he’d be racing in 2024. Just ask Remy Gardner, exiled to World Superbikes after a single season on a satellite Tech3 ride, or Raul Fernandez, who lucked into a satellite Aprilia seat alongside Miguel Oliveira, another guy you could just ask (who also happens to be the last person to win a race on a KTM (because we’re not counting sprints (right?))).

Zarco was at the forefront of all that, and while Brad Binder and Jack Miller seem to have settled in comfortably at KTM for the time being, Johann isn’t a backwoods hardhead; the guy plays guitar and chess, offers thoughtful answers in multiple languages, has a history of abuse by his first manager behind him to draw on for life experience. He is a complicated, sensitive, intelligent man, which bodes well for life beyond the paddock but can (and will) work against you at the highest echelons within it. A shock midseason separation that year felt like the end, felt like the sad vindication of what I’d suspected about that magnificent debut in Qatar aboard the Yamaha in 2017.

Some windows are so clean, you think they’re open when they’re really closed — but some skies are so dim, you forget the windows can open when they clear. A few lifeline rides at LCR Honda at the end of 2019 were enough to convince Avintia Ducati to take a chance on him for 2020, where he scored a podium in just the third race of a season where anything felt like it could happen. What happened, most importantly for Johann, was a renewal for 2021 with the satellite Pramac Ducati squad. Clawing at the glass with four second places in the first seven races of the year and fifth overall by season’s end. Three more podiums and eighth overall in 2022. Four more podiums in the first seven races of 2023. Forever clawing at the glass, wondering what the sky must smell like.

August: Alex Rins announces he’s leaving LCR Honda and moving to the factory Yamaha team to replace the listless Franco Morbidelli. Morbidelli announces he’s leaving to take the second Pramac Ducati ride. Zarco, it is finally announced, returns to LCR Honda. The Frenchman would swap the best bike in MotoGP for the worst one. With Bagnaia’s GP23 steadily improved and Zarco’s teammate Jorge Martin aggressively taking it to him for the championship in all the sprints and even some of the Sunday races, it felt like Zarco’s early-season form couldn’t match Ducati’s elite two riders now that they’d fully settled in. Consigned to the formidable, jostling Ducati ranks just beneath them, not to mention every other bloodthirsty maniac on the grid, a bonfire of good ideas, he would need something special to happen. Skies dimming, windows still closed.

With my Sam Browne on,

In the corner of this field,

No guts, no glory, yeah, right kid?

You couldn’t have scripted it, the best MotoGP race of the year. It was a beautiful, poetic thing to watch Jorge Martin take off on softer-compound tires he gambled could go the distance, leaving the field for dead in desperate pursuit of points to claw back on Pecco Bagnaia. The scrap in his wake was entertaining and, for most of the race, the remainder of the podium felt like it was gonna go the way of Pecco Bagnaia and Brad Binder, with Fabio Di Giannantonio thrown in the mix almost as a point of amusement.

The oft-heard refrain about Johann Zarco is that he has sensational late-race pace because only he can preserve his tires as well as he does, riding efficiently and burning a minimal amount of rubber; the other side of that coin means he’s always coming good too late to challenge for a win, eternally just another lap away from victory. But that’s why we watch, isn’t it?

I’d embed the video, but like seemingly everything else on the internet these days, you’ll have to settle for a Reddit link of the French commentary of the Australian Grand Prix’s final lap, a majestic motorcycling accordion snaking its way across picturesque seaside digs in which bikes strung out compress and string out again, just enough, in just the right order.

Life only comes in flashes of greatness. But how liberating this flash must’ve been, how good that backflip afterward must’ve felt, how decisively he made a forgettable season worth remembering, how perfectly Johann Zarco snuck through a chink in the armor of injustice, a crack in the open window to feel the sky, taste the air, forget the glass.

Johann Zarco, a MotoGP race winner.